Village occupied by troops – but they were British

A long-time resident remembers wartime years in West Bergholt.

In September 1939 at the outbreak of war, the villagers of West Bergholt, like countless others country-wide, blacked out their windows, tried on their gas masks, stocked up their larders and were ready for any eventuality.

Evacuees

First came the evacuees from East London who were quickly boarded out with willing foster families. They soon became integrated into the school and social life of the village. Coach loads of family members visited them on Sundays when “a blinkin’ good time” was had by all.

Everyone volunteered in some way or other to assist the war effort. A Home Guard unit was formed, ARP wardens patrolled the streets, fire watching groups were set up and first aid lessons arranged. Family and friends were bandaged and put in splints as “pretend” causalities. The Brewery had its own manual fire engine that extinguished many a mock blaze as it stood in readiness for the real thing.

Risk of Invasion

Before long, East Anglia became a possible invasion target. The evacuees were dispatched to the West of the country and West Bergholt prepared for an onslaught of troops. Several larger properties were commandeered for officers and the Orpen Memorial Hall housed the rank and file. The main hall was the sleeping quarters, but during the day the beds were rolled up neatly by the wall.

Various events were still held there but all civilians had to vacate the premises at a given time because the men had a “stand by your beds” inspection before lights out. There was an anti-aircraft post at the entrance to the village where the A12 motorway now crosses. One unit of Royal Engineers trained as paratroopers and many of those lads were lost at Arnhem.

Conscription

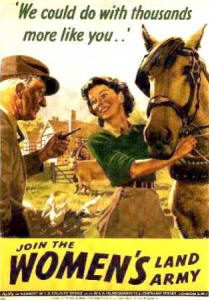

Initially only reservists were called for active service. The local young men were conscripted as and when their age and occupation dictated. Later on, women had to register for what was termed “work of national importance” in one of the armed forces, the Land Army, the nursing service or in a munitions factory. Many local farmers relied on the Land Army girls to keep the farms running.

During the construction of Wormingford airfield, lorries loaded with building material thundered through the village continuously. It became an American bomber base and when the bombing of Germany was at its height, people living in the flight path would count the droning planes going out and the often fewer ones coming back.

Bombing

West Bergholt did not escape the bombing entirely. In 1940, several houses were damaged and in 1941, the cottage at the Chitts Hill level crossing was demolished. On this occasion, two people were killed. Bombs also fell at Hillhouse farm and outbuildings were hit at Cooks Hall.

All the village organisations did their bit. The Conservative ladies knitted garments for the minesweeping crews. The WI members collected anything they could lay their hands on, including rabbit skins for Russia. National Savings groups were started and the government launched endless money-raising schemes. There was “Warships Week,” “The Spitfire Fund and “Salute the Soldier Week.” Through it all, the stalwart villagers “dug for victory” and were mindful that “careless talk costs lives.”

Welcome Home

A Welcome Home fund was set up by representatives of all local groups. The aim was to raise money to give every returning serviceman a small monetary gift. Those who did not return were to be commemorated on plaques to be put in suitable places, two of which were the Church and the Chapel. Nine names were recorded with ages ranging from 18 to 46.

The coastal seaside resorts were out of bounds to bathers because tank traps lined all the beaches. Leisure pursuits were limited. However, the cinema was in its heyday. There were five in Colchester and a ten shilling note (50p in today’s money) would buy two seats at The Regal and a meal of egg and chips afterwards – with enough change for the bus fare home.

Apart from personal losses and hardships, West Bergholt escaped unscathed. When the last “All Clear” sounded, the villagers packed away the blackout curtains and prepared to tackle – in some ways – the more difficult task of returning to normality.

Joyce Lucking

Village Bulletin – Issue 86,

June 2001